18 Jun 2025 [156] Antidepressant withdrawal syndrome – Update

Jump to: Abstract | Full Text | Plain Language Summary | Conclusions | References

Plain Language Summary

Antidepressant withdrawal

What patients and prescribers should know

Bottom line:

- Antidepressants can be helpful for some people; but starting or stopping requires care.

- Before starting, prescribers (doctors and nurse practitioners) should talk openly with patients about the risks of withdrawal, and make shared decisions about treatment and tapering.

- Knowing about the many types of possible withdrawal problems helps prescribers guide patients in stopping antidepressant drugs more safely.

What is antidepressant withdrawal and why is it important?

Antidepressant withdrawal is the problem some people have when they try to stop taking antidepressant medicines. It is now accepted that this can be much harder than many people and their prescribers realized. It is important for prescribers to help patients understand the withdrawal risks before patients decide if they want to start these medications.

What are antidepressant drugs?

Antidepressants are medications, supplied as pills or capsules. They are prescribed to help the patient manage strong feelings like being very sad for a long time (this is called depression) or feeling very worried and scared a lot without an obvious reason (this is called anxiety).

What happens when people take antidepressants?

The brain adapts itself to getting the medicine each day. This is called “tolerance”. To feel normal, over time the person needs to take this drug that the brain has come to rely on. This is called “dependence”. So, if the patient tries to stop the drug or take less of it, they can experience “withdrawal.”

Can people have withdrawal symptoms when stopping antidepressants?

Yes. Stopping antidepressants – especially when people use them for a longer time – can lead to withdrawal symptoms (problems). These symptoms can be both mental (like panic attacks or depression) and physical (like feeling dizzy or having trouble with balance). For some people, these problems can be very hard to handle and can last a long time.

Why does this happen?

Antidepressants can change how the brain works. When someone takes the drug for a longer time and then stops taking it suddenly or lowers the dose too quickly, the brain can struggle to adjust to not having the drug. This can cause withdrawal symptoms.

Are withdrawal symptoms the same as a return of depression or anxiety?

The symptoms may be different. Withdrawal symptoms can seem like a return of old problems, so it’s important for prescribers and pharmacists to know the difference.

How common is this issue?

We don’t know exactly how common. Using antidepressants for long periods of time, or years, makes withdrawal symptoms more likely. Some people can have withdrawal symptoms after much shorter periods, or even if they miss a dose. In the past, withdrawal risks were often downplayed. Now, we know better.

What should patients know before starting to take antidepressant drugs?

Patients should be informed clearly that:

- Their brain might get used to the medicine, making it hard to stop taking it later.

- Stopping can cause withdrawal problems that can be serious, last a long time, and sometimes be confused with relapse (return of the problems they were prescribed for).

- Prescribers should make sure that patients fully understand the risks and agree to the treatment before starting the medicine.

How should someone stop taking antidepressants safely?

Don’t stop suddenly! Tapering the amount (slowly and carefully lowering how much of the drug is taken over time) is the safest way. Sometimes this is done using special customized smaller doses, prepared by a pharmacist.

Abstract

Background: Antidepressants can cause tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal syndromes, often understated by the term “antidepressant discontinuation syndrome.” While they do not induce craving or compulsive use, brain adaptations to these drugs can make them hard to stop, especially after long-term use. Despite growing evidence of withdrawal risks, antidepressant prescriptions and long-term use continue to increase globally. The potential duration and severity of debilitating withdrawal symptoms, including akathisia, suicidality, and protracted withdrawal, have been minimized. This is partly due to commercially sponsored guidelines that relied on short-term clinical trial data.

Aims: Therapeutics Letter 156 updates evidence on antidepressant withdrawal syndrome, highlighting the potential for severe and prolonged symptoms. It encourages re-evaluation of prescribing practices, particularly in primary care, and suggests requirements for informed consent before patients start an antidepressant. Therapeutics Letter 156 also aims to distinguish withdrawal from relapse of an underlying mental illness. This topic will be explored further in Therapeutics Letter 157, which will examine deprescribing strategies in more detail, including “hyperbolic tapering.”

Recommendations: Prescribers should ensure patients provide fully informed consent before starting antidepressants, explicitly discussing the risks of tolerance, dependence, and potentially severe, prolonged, or even irreversible withdrawal symptoms. This includes warning about new-onset suicidality and chronic akathisia. Informed consent should be documented formally, ideally using consent forms tailored to the prescriber’s practice. Patients should also be informed about the challenges of tapering, including the current lack of suitable drug formulations, and potential difficulties in finding experienced clinical support if withdrawal problems are severe.

Antidepressant withdrawal syndrome – Update

Vignette: A 53-year-old woman is new to your practice. Since the birth of her first child 19 years ago, she has taken extended release venlafaxine 75 mg/day for post-partum depression. At first she found the medication quite helpful. Now she wonders if her emotional blunting, sexual dysfunction, weight gain and mental fog could be due to the drug. She would like to stop venlafaxine, but is worried because of a difficult and ultimately unsuccessful attempt 5 years ago. After reducing the daily dose to the smallest capsule of 37.5 mg, she felt dizzy, experienced the first panic attacks of her life, and had trouble walking in a straight line. She says that when she started treatment after giving birth, she was not warned about the possible effects of withdrawal. A friend, who tried but failed to stop citalopram, urged her to consult you rather than trying to stop “cold turkey” on her own. How will you assist your new patient?

Summary and Conclusions

- Like other drugs that target the brain, antidepressants induce pharmacological tolerance and dependence. Not everyone finds it hard to stop an antidepressant, but for some the experience can be difficult and/or prolonged.

- Before they can provide informed consent to treatment, patients need to understand that withdrawal may be difficult. Formal documentation of consent could protect both patient and prescriber.

- Awareness of the range of withdrawal symptoms, and the possibility of protracted withdrawal, can facilitate safe deprescribing.

Introduction

Clinicians routinely alert patients to both the potential benefits and harms of drug therapy, especially for treatments that risk significant harms. Examples include insulins, steroid hormones, oral contraceptives, anticoagulants, cancer chemotherapy, and drugs with the potential to cause dependence or abuse.

Like benzodiazepines and opioids, antidepressants cause tolerance, dependence and withdrawal syndromes. The term “antidepressant discontinuation syndrome” is a euphemism that understates clinical problems patients can experience after dose reductions or deprescription.1,2 Antidepressants do not cause craving or compulsive drug-seeking, but the brain adapts to their pharmacological effects. Over a few weeks to months, this can make antidepressants difficult, or even impossible, to stop.3,4

In 2018, Therapeutics Letter 112 addressed the topic of antidepressant withdrawal syndrome and its management.5 The Letter emphasized that informed consent to treatment implies that patients should be alerted to this risk before starting drug treatment. It is also important to inform patients that most mild-to-moderate episodes of anxiety and depression will resolve on their own, and that non-drug treatments such as CBT and/or mindfulness or physical activity may be equally or more effective.

Since 2018, understanding of withdrawal has increased, yet prescriptions and long-term use of antidepressants continue to rise. In England, prescriptions doubled from 2010 to 2024, now including about 20% of the population, half of whom take antidepressants long-term.6 According to United States (U.S.) national surveys, antidepressant use increased from less than 8% of people aged 12 years or older in 1999-2002 to nearly 13% by 2011-2014, and 19% in women over 60. More than two-thirds of Americans taking an antidepressant had done so for more than 2 years, and one-quarter for more than 10 years.7 About 14% of Australians take antidepressants, half of them for longer than 12 months.8

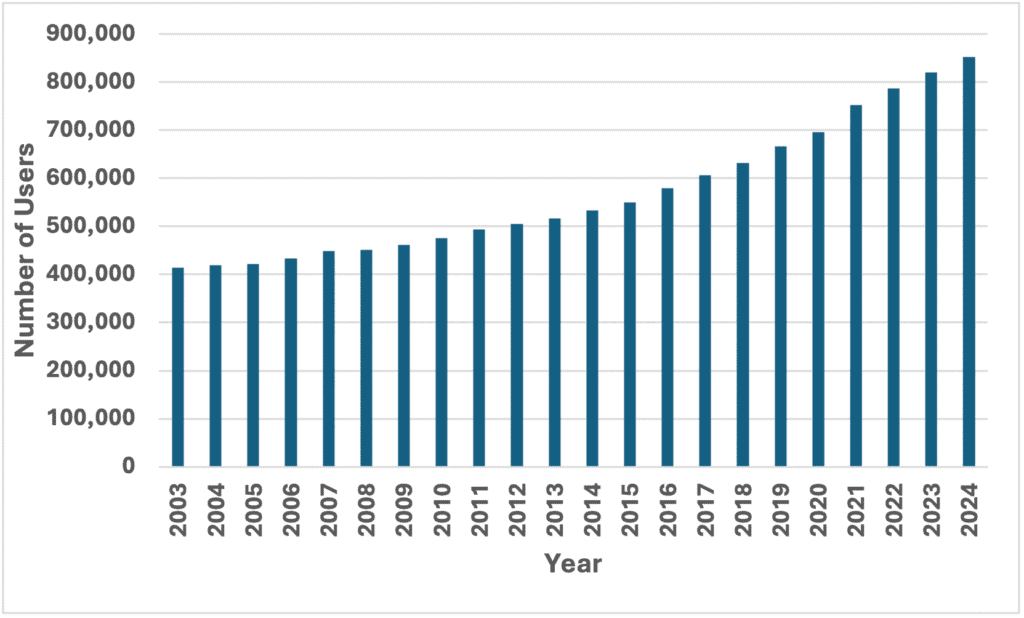

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show similar trends in British Columbia, although the clinical indications could include anxiety and other diagnoses, as well as depression. During 2024, an antidepressant was dispensed to over 852,429 individual British Columbians, about 15% of BC’s population of 5,722,318. Per capita dispensing increased by 50% from 2003, when 418,231 of 4,123,937 British Columbians, or 10%, received an antidepressant. These numbers do not include federally insured residents, nor beneficiaries of the First Nations Health Benefit Plan, who would increase the totals and percentages.

Dispensing of antidepressants for at least 6 months grew even faster than total dispensing, from 235,691 people during 2003 to 620,831 during 2024. The 263% increase over 21 years means that almost 11% of British Columbians now take antidepressants long-term.

Figure 1: Number of British Columbians dispensed an antidepressant 2003-2024

Figure 2: British Columbians dispensed an antidepressant for ≥6 months 2003-2024

Notes:

- Source data exclude federally insured residents and beneficiaries of the First Nations Health Benefit Plan.

- Antidepressant users had active Medical Service Plan coverage during the relevant calendar year.

- Figure 2 includes antidepressant users who received at least 180 days supply of any antidepressant (switching allowed) during the relevant calendar year.

- Antidepressants included: tricyclics/tetracyclic (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin {>25mg dose}, imipramine, nortriptyline, trimipramine, maprotiline), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, levomilnacipran, venlafaxine), and other antidepressants (bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodone, vilazodone, vortioxetine). Excluded: low dose doxepin (3mg, 6mg), esketamine, MAO inhibitors, nefazodone, tryptophan.

Because most antidepressant prescriptions are initiated in primary care – and not always after thorough diagnosis and documentation – there is growing recognition of the need to re-evaluate how primary care clinicians prescribe.9

This Letter updates evidence about antidepressant withdrawal, and proposes requirements for informed consent to antidepressant treatment. Some clinicians who are trying to help their patients may find the information upsetting – because it reflects a paradigm shift in understanding of antidepressants. Therapeutics Letter 157 will focus on how to avoid or manage the clinical problem of antidepressant withdrawal.

Withdrawal: a corollary of tolerance and dependence

Soon after discovery of the first antidepressant drugs, psychiatrists recognized withdrawal symptoms in patients who reduced or stopped treatment. By 1959, a Canadian report described withdrawal from imipramine, the first tricyclic antidepressant.10 The chief symptoms were nausea, vomiting, dizziness, chills, and great anxiety. U.S. pioneers of imipramine therapy reported in 1961: “The intensity of physiological symptoms is directly proportional to the duration of drug administration and the abruptness of withdrawal.” Over half of their first patients experienced withdrawal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, dizziness, coryza (runny nose), muscular pains, and malaise.11

Fluoxetine, the first SSRI antidepressant, was not long on the market before a 1991 case report documented distressing symptoms that occurred 2 days after cessation of a 6-month drug treatment.12 The term “withdrawal syndrome” was used in 1996 by Pfizer Inc., the manufacturer of sertraline; however Pfizer was reluctant to disclose this to Norwegian regulators.13 Eli Lilly & Company (the inventor of fluoxetine) was also alert to the issue, but preferred to popularize the more benign language “discontinuation syndrome” in the non-peer-reviewed proceedings of a “closed symposium” it sponsored for influential psychiatrists in 1996.14 The Introduction to these proceedings (published as a 1997 Supplement to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry) acknowledged that withdrawal occurred with many antidepressants – and that the syndrome could be prolonged and severe. It emphasized that withdrawal was often misdiagnosed – or recognized only after expensive consultations and investigations.15

Today, antidepressant withdrawal syndrome is acknowledged as possible after even brief exposure to any antidepressant.2,3,4 The World Health Organization’s database of spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports includes records of withdrawal from at least 28 different antidepressants. Paroxetine, duloxetine, venlafaxine/desvenlafaxine, and sertraline are represented disproportionately in the database; and all but sertraline are reported to have an odds ratio exceeding that of the opioid buprenorphine.

Characteristics of withdrawal

Physical and psychological symptoms can manifest after stopping or reducing a dose, or even after missing doses.18,19 Although various explanations are proposed,20-22 withdrawal mechanisms are no better elucidated than the actions of antidepressants. Changes in the availability or effects of neurotransmitters have diverse physiological consequences.21-24 During daily drug treatment, homeostatic adaptations of the brain and body gradually minimise these effects; but when drug treatment is reduced or stopped, brain re-adaptation is not immediate, and may take months or years.21,25

Neurotransmission modulated by antidepressants affects myriad biological processes: more than 80 different withdrawal symptoms are recorded.26 These are often categorized into emotional symptoms or physical symptoms and signs.

Acute and persistent symptoms include low mood, anxiety, panic attacks, obsessive thinking, crying, emotional lability, “dizziness,” headache, increased dreaming or nightmares, insomnia, irritability, myoclonus, nausea, electric shocks (“zaps”), tremor, flu-like symptoms, imbalance, sensory disturbances, akathisia, and suicidal feelings.3,26-29

Three clinically important withdrawal syndromes typically arise after rapid discontinuation of antidepressants (Table 1).

Table 1: Clinically important antidepressant withdrawal syndromes

Neuropsychiatric and somatic symptoms most characteristic of withdrawal include “electric shocks/brain zaps,” akathisia, dizziness or light-headedness, nausea/vomiting, vertigo, gait and coordination problems, or increased sensitivity to light and noise.29 Protracted antidepressant withdrawal can be misdiagnosed as the return of a patient’s underlying mental illness,29 or a new mental or physical health condition.31 Derived from patient self-reported experiences, the Discriminatory Antidepressant Withdrawal Symptom Scale (“DAWSS”), proposed in 2024,29 may help to distinguish protracted withdrawal from relapse. This syndrome can be so debilitating that people lose jobs, relationships, or die by suicide.31,32

An analogous syndrome of protracted withdrawal from benzodiazepines was recognized by the 1980s, and explored by U.S. psychiatrists in a 2018-2019 internet survey (N=1,207).33 In 2023 the investigators characterized a constellation of new but enduring symptoms that appeared to have arisen de novo from benzodiazepine use, sometimes persisting for at least a year after benzodiazepines had been stopped. To distinguish this from acute withdrawal, they proposed the term “benzodiazepine-induced neurological dysfunction.”34

Studies of antidepressant drugs usually do not follow patients for long periods, or after drug discontinuation. Thus, the proportion of people who experience protracted withdrawal is unknown. A 2021-2022 survey of patients in London, England provides a clue. The patients surveyed were receiving primary care “Talking Therapies”, and had tried to stop an antidepressant (N=310). About 25% of the respondents who had taken an antidepressant for more than 2 years reported “severe” withdrawal effects after stopping.35

Withdrawal differs from relapse

In primary care, most people for whom antidepressants are prescribed do not have a long-term or recurrent underlying condition that can be expected to relapse. More often, a drug is first prescribed after a life crisis such as stress related to education, divorce, job loss, or death of a loved one. Therefore, when an antidepressant is stopped, or the dose is reduced, distinguishing withdrawal from a relapse of the original clinical problem is essential to avoid unnecessarily prolonged drug treatment,35 as well as to prevent long-term harms (Table 2).

Table 2: Distinguishing antidepressant withdrawal from relapse of underlying condition

Conflicted early guidelines minimized withdrawal problems

At the 1996 “closed symposium” sponsored by Eli Lilly & Company, psychiatric key opinion leaders described withdrawal effects as “generally mild, short lived, and self-limiting.”38 They did acknowledge serious outcomes such as hospitalization for suspected myocardial infarction during withdrawal from venlafaxine, and suggested that patients be asked routinely if there are medications they have stopped taking in the past few days.

Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (maker of venlafaxine) sponsored a similar meeting in 2004. In proceedings published in 2006 (as a non-peer-reviewed journal supplement), Wyeth’s “Consensus Panel” better acknowledged the frequency and potential severity of “discontinuation,” noting that withdrawal symptoms from paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine had been observed within 12 to 24 hours after a missed dose. However, while the authors recommended routine tapering of antidepressants instead of abrupt cessation, they advocated that “clinicians should reassure their patients that this syndrome is easily manageable.”39

In the United Kingdom (U.K.) guidelines, this benign characterization of withdrawal as “usually mild and self-limiting over about one week” persisted until 2019.40 The 2024 update of Canadian depression guidelines (CANMAT) recognized that “up to 50% of patients may experience discontinuation symptoms when stopping long-term use of antidepressants, especially with abrupt stopping.”41 However, like their U.S. predecessors, the authors characterized withdrawal symptoms as likely to occur within a few days of decreasing or stopping a drug, as “mild or moderate in severity,” and as expected to resolve “within a few weeks.”

Has the ‘evidence’ changed?

Our review of evidence found that commercially sponsored “consensus recommendations” related to antidepressant withdrawal (like many guidelines in psychiatry), were affected by conflicts of interest. They also rely on withdrawal effects observed after only 8-12 weeks of antidepressant exposure during randomized controlled trials (RCTs).42 Yet most patients take antidepressants for much longer. The BBC found that from 2015/16 to 2019/20, over one-quarter of the more than 8 million people in England taking antidepressants had done so for 5 years.13 And an ongoing Australian deprescribing cluster RCT (RELEASE) found, by screening more than 12,000 patients from 26 general practice clinics, that 50% had used an antidepressant for at least 12 months.9

Longer duration of antidepressant use greatly increases the likelihood, severity, and potential duration of withdrawal effects.21,43 For example, of respondents reporting withdrawal effects in a 2013 online survey in New Zealand (N=1,367), 28% of those who had used antidepressants for less than 3 to 6 months reported withdrawal effects, of which 18% were “moderate/severe.”44 But two-thirds of people treated for at least 3 years (N=701) reported withdrawal effects, including over half who characterized withdrawal as “moderate/severe.” The 2021-2022 survey of Londoners who had ever tried to stop an antidepressant (N=310, 79% female) found that 64% of those who had taken drug therapy for at least 2 years reported “moderate or severe withdrawal.” One in eight said the effects lasted for over a year.35

An early double-blind RCT in the U.S. examined SSRI discontinuation over 5 to 8 days, after a mean of 11 months of use (N=192). It identified withdrawal effects in 60% and 66% of patients taking sertraline or paroxetine, versus 14% of those taking fluoxetine – a much longer acting drug.45 In contrast, a 2024 systematic review of shorter RCTs estimated an absolute risk increase of about 15% for withdrawal symptoms after stopping active drug therapy. The number needed to harm (NNH) was estimated at 6 to 7 patients. For severe withdrawal symptoms, the NNH was estimated at 35.46 A 2025 systematic review published after we first posted Letter 156 concluded that “on average, those who discontinue antidepressants experience 1 more discontinuation symptom compared to placebo or continuation of antidepressants, which is below the threshold for clinically important discontinuation syndrome.” However, it relies on 11 short RCTs (10 of 8-12 weeks and 1 of 26 weeks using agomelatine, a drug not known to have a withdrawal syndrome), and analysis of withdrawal symptoms at 1 week after study drugs were stopped.47 But evaluations of longer RCTs indicated that about 50% of patients experienced withdrawal effects, of which about half were reported as severe.43,48

Finally, an influential RCT in the U.K. examined antidepressant deprescribing in patients who had taken citalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, or mirtazapine for more than 2 years (N=150 general practices, 478 patients).49 Participants randomized to stop the drugs experienced significantly more withdrawal symptoms for at least 9 months of the 12-month trial.50

What constitutes informed consent to treatment?

For any proposed therapy, a patient’s ability to provide informed consent requires access to information about potential harms as well as benefits. For antidepressants, as when starting a benzodiazepine, an opioid, or a corticosteroid, this includes understanding that it may be very difficult to stop, and that long-lasting withdrawal symptoms are possible. Potentially these can be as severe as new-onset suicidality, and persistent akathisia. For some people, withdrawal symptoms are irreversible or so debilitating that an antidepressant cannot be stopped.3

This issue has unique implications for women of reproductive age, because antidepressant use during a planned or unexpected pregnancy also has implications for the fetus and neonate. Stopping an antidepressant during pregnancy may be especially challenging.

Canadian and other prescribers and patients should also appreciate that drug formulations to facilitate tapering and safe discontinuation of antidepressants are not currently available. To reduce dose slowly and gradually, patients may have to crush tablets, or dissolve them in water and use syringes. They should be informed that it may be challenging to identify a clinician with expertise and experience in stopping psychotropic drugs. Dedicated deprescribing services may not be available to assist,51 although BC’s Primary Care Network pharmacists may be helpful.

The Appendix (available as a sample PDF or editable Word document) is a modifiable Informed Consent to Start an Antidepressant form, adapted from opioid and benzodiazepine treatment agreements recommended by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia.52,53 Allowing patients time to review and consider such a form, before prescribing an antidepressant, might facilitate true informed consent and mitigate societal pressures for excessive prescribing.

Stopping antidepressants safely

Therapeutics Letter 157, to be posted in July 2025, will review what is known about deprescribing antidepressants, including the “hyperbolic tapering” approach for people who experience or fear a difficult withdrawal syndrome.

Vignette resolution: Having taken venlafaxine 75 mg/day for 19 years, and given the symptoms she experienced after a previous attempt to reduce the dose, your patient is at high risk for a withdrawal syndrome if she stops venlafaxine precipitately. But she is keen to try again, and you have the chance to plan a more fruitful approach. After thorough discussion, you provide her with written information,54 and plan to arrange compounding of progressively smaller doses by a suitable pharmacist. At the next visit, you and your patient can review options and decide on a controlled and supervised dose tapering plan.

The Therapeutics Letter is a member of the International Society of Drug Bulletins (ISDB), a world-wide network of independent drug bulletins that aims to promote international exchange of quality information on drugs and therapeutics.

The Therapeutics Letter is a member of the International Society of Drug Bulletins (ISDB), a world-wide network of independent drug bulletins that aims to promote international exchange of quality information on drugs and therapeutics.Data References and Disclaimer

The BC Ministry of Health approved access to and use of BC data. The following data sets were used: PharmaNet (ClaimsHist), Client Roster. All inferences, opinions and conclusions drawn in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the data stewards.

References

- Massabki I, Abi-Jaoude E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor ‘discontinuation syndrome’ or withdrawal. British Journal of Psychiatry 2020; 218(3):168-71. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.2019.269

- Fava GA, Cosci F. Understanding and managing withdrawal syndromes after discontinuation of antidepressant drugs. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2019; 80:6. DOI: 10.4088/JCP.19com12794

- Horowitz M, Taylor D. The Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry: Antidepressants, Benzodiazepines, Gabapentinoids and Z-drugs. 2024; https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&citation_for_view=sEcbBuUAAAAJ:abG-DnoFyZgC

- Horowitz MA, Taylor D. Addiction and physical dependence are not the same thing. The Lancet. Psychiatry 2023; 10(8):e23. DOI: 10.1016/S2215-366(23)00230-4

- Therapeutics Initiative. Antidepressant withdrawal syndrome. Therapeutics Letter 2018 (May-June) 112. https://ti.ubc.ca/letter112

- Avery T. Striking the right balance with antidepressant prescribing. Patient Safety Commissioner for England 2024; https://www.patientsafetycommissioner.org.uk/striking-the-right-balance-with-antidepressant-prescribing/

- Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant use among persons aged 12 and over: United States, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief 2017; 283:1-8. PMID: 29155679

- Wallis KA, Donald M, Horowitz M, et al. RELEASE (REdressing Long-tErm Antidepressant uSE): protocol for a 3-arm pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial effectiveness-implementation hybrid type-1 in general practice. Trials 2023; 24(1):615. DOI: 10.1186/s13063-023-07646-w

- Wallis KA, King A, Moncrieff J. Antidepressant prescribing in Australian primary care: time to reevaluate. Medical Journal of Australia 2025; 222(9):430-2. DOI: 10.5694/mja2.52645

- Mann AM, Macpherson AS. Clinical experience with imipramine (G 22355) in the treatment of depression. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal 1959; 4(1):38-47. DOI: 10.1177/070674375900400111

- Kramer JC, Klein DF, Fink M. Withdrawal symptoms following discontinuation of imipramine therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry 1961; 118:549-50. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.118.6.549

- Stoukides JA, Stoukides CA. Extrapyramidal symptoms upon discontinuation of fluoxetine. American Journal of Psychiatry 1991; 148(9):1263. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.148.9.1263a

- Shraer R, Hix C, Harris L. Antidepressants: Two million taking them for five years or more. BBC Panorama 2023; https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-65825012

- Multiple authors. SSRI Discontinuation Events (closed symposium December 17, 1996 sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1997; 58(suppl 7):1-40. https://www.psychiatrist.com/jcp/archive/1997/58/suppl%207/

- Schatzberg AF. Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndrome: An update on serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1997; 58(suppl 7):3-4. https://www.psychiatrist.com/jcp/introductionantidepressant-discontinuation-syndrome/

- Quilichini JB, Revet A, Garcia P, et al. Comparative effects of 15 antidepressants on the risk of withdrawal syndrome: A real-world study using the WHO pharmacovigilance database. Journal of Affective Disorders 2022; 297:189-93. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.041

- Gastaldon C, Schoretsanitis G, Arzenton E, et al. Withdrawal syndrome following discontinuation of 28 antidepressants: Pharmacovigilance analysis of 31,688 reports from the WHO Spontaneous Reporting Database. Drug Safety 2022; 45(12):1539-49. DOI: 10.1007/s40264-022-01246-4

- Horowitz MA, Taylor D. Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. The Lancet. Psychiatry 2019; 6(6):538–46. DOI: 10.1007/S2215-0366(19)30032-X

- Black K, Shea C, Dursun S, Kutcher S. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience 2000; 25(3):255–61. PMID: 10863885

- Renoir T. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant treatment discontinuation syndrome: A review of the clinical evidence and the possible mechanisms involved. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2013; 4:45. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00045

- Horowitz MA, Framer A, Hengartner MP, et al. Estimating risk of antidepressant withdrawal from a review of published data. CNS Drugs 2023; 37(2):143-57. DOI: 10.1007/s40263-022-00960-y

- Sharp T, Collins H. Mechanisms of SSRI therapy and discontinuation. Current Topics in Behavioral Neuroscience 2024; 66:21–47. DOI: 10.1007/7854_2023_452

- Reidenberg MM. Drug discontinuation effects are part of the pharmacology of a drug. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics 2011; 339(2):324–8. DOI: 10.1124/jpet.111.183285

- Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L. Effects of treatment discontinuation in clinical psychopharmacology. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics 2019; 88(2):65-70. DOI: 10.1159/000497334

- Fava GA, Gatti A, Belaise C, et al. Withdrawal symptoms after selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: A systematic review. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics 2015; 84(2):72–81. DOI: 10.1159/000370338

- Cosci F, Chouinard G. Acute and persistent withdrawal syndromes following discontinuation of psychotropic medications. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics 2020; 89(5):283–306. DOI: 10.1159/000506868

- Horowitz MA, Taylor D. Distinguishing relapse from antidepressant withdrawal: clinical practice and antidepressant discontinuation studies. BJPsych Advances 2022; 28(5):297–311. DOI: 10.1192/bja.2021.62

- Akathisia Alliance for Education and Research. Akathisia: General information. Web site 2025; https://akathisiaalliance.org/about-akathisia/

- Moncrieff J, Read J, Horowitz MA. The nature and impact of antidepressant withdrawal symptoms and proposal of the Discriminatory Antidepressant Withdrawal Symptoms Scale (DAWSS). Journal of Affective Disorders Reports 2024; 16:100765. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadr.2024.100765

- Horowitz MA, Davies J. Hidden costs: the clinical and research pitfalls of mistaking antidepressant withdrawal for relapse. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics 2024; 94(1):3-7. DOI: 10.1159/000542437

- Guy A, Brown M, Lewis S, Horowitz M. The “patient voice”: patients who experience antidepressant withdrawal symptoms are often dismissed, or misdiagnosed with relapse, or a new medical condition. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology 2020; 10:2045125320967183. DOI: 10.1177/2045125320967183

- Hengartner MP, Schulthess L, Sorensen A, Framer A. Protracted withdrawal syndrome after stopping antidepressants: a descriptive quantitative analysis of consumer narratives from a large internet forum. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology 2020; 10:2045125320980573. DOI: 10.1177/2045125320980573

- Reid Finlayson AJ, Macoubrie J, Huff C, et al. Experiences with benzodiazepine use, tapering, and discontinuation: an Internet survey. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology 2022; 12:20451253221082386. DOI: 10.1177/20451253221082386

- Ritvo AD, Foster DE, Huff C, et al. Long-term consequences of benzodiazepine-induced neurological dysfunction: A survey. PLoS One 2023; 18(6):e0285584. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285584

- Horowitz M, Buckman JEJ, Saunders R et al. Antidepressants withdrawal effects and duration of use: a survey of patients enrolled in primary care psychotherapy services. Psychiatry Research 2025; 116497. DOI: 1016/j.psychres.2025.1216497

- Stockmann T, Odegbaro D, Timimi S, Moncrieff J. SSRI and SNRI withdrawal symptoms reported on an internet forum. International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine 2018; 29(3-4):175–80. DOI: 10.3233/JRS-180

- Framer A. What I have learnt from helping thousands of people taper off psychotropic medications. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology 2021; 11:2045125321991274. DOI: 10.1177/2045125321991274

- Rosenbaum JF, Zajecka J. Clinical management of antidepressant discontinuation. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1997; 58(Suppl 7):37-40. PMID: 9219493

- Schatzberg AF, Blier P, Delgado PL, et al. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome: Consensus panel recommendations for clinical management and additional research. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2006; 67(Suppl 4):27-30. PMID: 16683860

- Iacobucci G. NICE updates antidepressant guidelines to reflect severity and length of withdrawal symptoms. BMJ 2019; 367:l6103. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.l6103

- Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Adams C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 Update on clinical guidelines for management of major depressive disorder in adults. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2024; 69(9):641-87. DOI: 10.1177/07067437241245384

- Baldwin DS, Montgomery SA, Nil R, Lader M. Discontinuation symptoms in depression and anxiety disorders. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2007; 10(1):73–84. DOI: 10.1017/S1461145705006358

- Zhang MM, Tan X, Zheng YB, et al. Incidence and risk factors of antidepressant withdrawal symptoms: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Molecular Psychiatry 2025; 30(5):1758-69. DOI: 10.1038/s41380-024-02782-4

- Read J, Cartwright C, Gibson K. How many of 1829 antidepressant users report withdrawal effects or addiction? International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 2018; 27(6):1805-15. DOI: 10.1111/inm.12488

- Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Hoog SL, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Biological Psychiatry 1998; 44(2):77–87. DOI: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00126-7

- Henssler J, Schmidt Y, Schmidt U, et al. Incidence of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Psychiatry 2024; 11(7):526-35. DOI: 10.1016/S2215-0366(24)00133-0

- Kalfas M, Tsapekos D, Butler M, et al. Incidence and nature of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, Published online July 09, 2025. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2025.1362

- Davies J, Read J. A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: Are guidelines evidence-based? Addictive Behaviors 2019; 97:111–21. DOI: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.027

- Lewis G, Marston L, Duffy L, et al. Maintenance or discontinuation of antidepressants in primary care. New England Journal of Medicine 2021; 385(14):1257-67. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2106356

- Mahase E. Half of people who stopped long term antidepressants relapsed within a year, study finds. BMJ 2021; 374:n2403. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.n2403

- Read J, Moncrieff J, Horowitz MA. Designing withdrawal support services for antidepressant users: Patients’ views on existing services and what they really need. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2023; 161:298–306. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.03.013

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia. Opioid treatment agreement. Website 2025; https://www.cpsbc.ca/files/pdf/PRP-Sample-Opioid-Treatment-Agreement.pdf

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia. Benzodiazepine treatment agreement. Website 2025; https://www.cpsbc.ca/files/pdf/PRP-Sample-Benzodiazepine-Treatment-Agreement.pdf

- Gardner D. Understanding antidepressant medications Part 2: When and how to safely stop them. Canadian Medication Appropriateness and Deprescribing Network 2025; https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5836f01fe6f2e1fa62c11f08/t/679d15c7d5442f445e3ee980/1738347977229/article-antidepressants_part2_EN-2025-01-28.pdf

Thomas L. Perry

Posted at 22:20h, 16 JulyThree weeks after we posted Therapeutics Letter 156: Antidepressant Withdrawal Syndrome – Update, the journal JAMA Psychiatry published a new analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in which antidepressants were stopped.[1,2] We have been able to update Letter 156 from its original posting of June 19, 2025, to include a brief reference to this new meta-analysis of Kalfas et al.

The new systematic review and meta-analysis includes some unpublished data about withdrawal symptoms. But it is based primarily on short-term RCTs that were the subject of earlier reviews and meta-analyses.

Consistent with earlier analyses, the authors found that withdrawal after 8-12 weeks of treatment with antidepressants involved few symptoms. These studies were mostly designed and/or conducted and analyzed by manufacturers of antidepressants.

The authors also report that relapse of depression is unusual in the first week after stopping an antidepressant. However, this observation is based on depression reported spontaneously as an adverse event – in studies that were not designed to detect depression relapse. Other studies show clear evidence that depressed mood can emerge as a common effect of withdrawal from antidepressants – even in people who have not previously experienced depression.[3]

News reports of the JAMA Psychiatry study provoked many online criticisms that it underestimates the problems of withdrawal, including from people who report having experienced challenging withdrawal symptoms.[4,5] The Antidepressant Education Coalition posted a well written letter to JAMA Psychiatry requesting a correction to Kalfas et al to indicate that it is based on short term trials.[6] Readers may be interested in the range of opinion and personal experience of prescribers and patients reflected at these websites.

The Kalfas et al JAMA Psychiatry meta-analysis also relies heavily on RCTs of agomelatine, a little-used drug approved in Europe and Australia, but not approved in North America. Unlike the other drugs discussed in Therapeutics Letter 156 and the upcoming Therapeutics Letter 157, agomelatine is not believed to induce dependence, nor to cause withdrawal.

We interpret the new study as confirming a general consensus that for most people, short-term use of antidepressants does not cause severe withdrawal. However the new review is not relevant to effects of longer term use, the cause of the greatest difficulties for patients. Other RCTs with longer exposure time (at least several months) have found that at least 60% of antidepressant users experience withdrawal effects on stopping.[7]

We will consider posting Comments in response to Therapeutics Letter 156 and Therapeutics Letter 157: How to stop antidepressants from readers of the JAMA Psychiatry article. We typically post all comments received, providing:

Thomas L. Perry MD, FRCPC

Editor, Therapeutics Letter

Dr. Perry’s disclosure is posted here: https://www.ti.ubc.ca/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/TomPerry_COI_June_2021.pdf There is no change from 2021.

References

Rapid responses: https://www.bmj.com/content/390/bmj.r1432/rapid-responses

Mark Horowitz

Posted at 22:30h, 16 JulyThe new systematic review and meta-analysis of Kalfas et al [1] shows that antidepressants cause physical dependence and withdrawal effects after a few weeks (8-12 weeks) of use, but the withdrawal symptoms are mostly not large in number.[2] There are still patients who suffer severe and long-lasting withdrawal after short term use, but much more rarely than long term users.[3]

However this study does not answer the key question in the field about what happens to long term users. There are up to 4 million people in the UK and 25 million in the US who use antidepressants for 2 years or more.[3]

Indeed Kalfas et al present the same information, based on many of the same studies, on which guidelines like those of NICE in the UK and others around the world have been based for years – which has been so problematic for long-term users.[3] An analysis published in 2007 was essentially similar.[4]

The new review has added a few more randomized clinical trials (RCTs). Two things are new:

a) a meta-regression, finding no relationship between duration of exposure and risk of withdrawal;

b) a sweeping conclusion that significant withdrawal effects do not generally occur for people stopping antidepressants.

In the main analysis of the publication, the authors do not report the duration of use of the RCTs (this is buried in the Supplemental Online Content).[1] The main analysis reports a 1.08 point Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms (DESS) increase at one week (after 8-12 weeks of use). I reproduce them below. The meta-regression they conduct is almost certainly hampered by a floor effect (all short-term studies). The longest study included in this analysis and meta-regression was 26 weeks, involving only the antidepressant agomelatine, that is not known to have withdrawal issues.

One could expect that longer term use creates worse problems for withdrawal, as for every other drug known – and this has been borne out in studies. For example, one study found that people who use antidepressants for more than two years have ten times the risk of withdrawal as people who use these drugs for less than 6 months.[3] So the examination of these shorter term studies is not informative for longer term users. A double-blind randomised controlled trial found that 60% or more of people who use sertraline or paroxetine experienced withdrawal effects after 11 months of use on average.[5]

Other limitations to this review are the fact that it subtracts placebo withdrawal from antidepressant withdrawal. It has been shown that antidepressant withdrawal is five times as likely to be severe as withdrawal of placebo.[6] Thus, the approach of Kalfas et al will tend to minimise the character of antidepressant withdrawal effects. They also overlook the fact that just one severe withdrawal symptom (nausea, headache, panic) could be very impairing.

The authors also conclude erroneously that depressed mood on stopping must represent relapse, rather than a withdrawal effect, as they found little evidence in their approach for depressed mood. However, their approach relied mostly on spontaneous adverse effect reporting, known to under-estimate detection. There is considerable evidence from other studies that depressed mood is a very common withdrawal effect – when assessed systematically. For example, in a carefully conducted study of withdrawal,[5] the incidence of a depressive syndrome based on a >8 point increase on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale was manifold higher (30% for sertraline and 36% for paroxetine) than the pooled estimates for depressed mood (1.29%) in Kalfas et al.

Overall, this study shows that just weeks of exposure to antidepressants causes withdrawal effects, but that the issues are not as numerous as for long-term users. It is another example of the general message that antidepressants should be used as briefly as possible, so as not to increase withdrawal risks.

The main results are based on 11 studies (shown in Figure 2 and reported in abstract)

Number Study Drugs Duration of use

1 Boulenger 2014 Duloxetine, vortioxetine 8 weeks

2 Boyer 2008 Desvenlafaxine 8 weeks

3 Jacobsen 2015 Vortioxetine 8 weeks

4 Liebowitz 2008 Desvenlafaxine 8 weeks

5 Mahableshwarkar 2015 Duloxetine, vortioxetine 8 weeks

6 Montgomery 2004 Agomelatine, paroxetine 12 weeks

7 Montgomery 2005 Escitalopram 12 weeks

8 Rickels 2010 Desvenlafaxine 12 weeks

9 Stein 2008 Agomelatine 12 weeks

10 Stein 2012 Agomelatine 26 weeks

11 Tourian 2009 Desvenlafaxine, duloxetine 8 weeks

Mark Horowitz BA BSc MSc GDPsych MBBS PhD, London, UK

Dr. Horowitz submitted with this comment a completed ICMJE disclosure form.[7]

References

1. Kalfas M, Tsapekos D, Butler M, et al. Incidence and nature of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2025; published online July 9. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2025.1362

2. Moncrieff J, Horowitz M. Antidepressant withdrawal: new review downplays symptoms but misses the mark for long-term use. The Conversation. 2025. http://theconversation.com/antidepressant-withdrawal-new-review-downplays-symptoms-but-misses-the-mark-for-long-term-use-260708 (accessed July 16, 2025).

3. Horowitz MA, Buckman JEJ, Saunders R, Aguirre E, Davies J, Moncrieff J. Antidepressants withdrawal effects and duration of use: a survey of patients enrolled in primary care psychotherapy services. Psychiatry Res 2025; : 116497.

4. Baldwin DS, Montgomery SA, Nil R, Lader M. Discontinuation symptoms in depression and anxiety disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2007; 10: 73–84.

5. Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Hoog SL, Ascroft RC, Krebs WB. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44: 77–87.

6. Henssler J, Schmidt Y, Schmidt U, Schwarzer G, Bschor T, Baethge C. Incidence of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2024; 11: 526–35.

7. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors disclosure of Dr. Mark Horowitz, July 16, 2025. [LINK]